Last week the NYT ran another feature by Roni Caryn Rabin: After Mastectomies, an Unexpected Blow: Numb New Breasts. Roni is one of the few mainstream journalists asking tough questions about breast cancer realities. Last fall, she penned a thought-provoking piece about folks who go flat post-breast cancer. Now, her first follow-up is a well considered examination of a common problem – numbness after reconstruction.

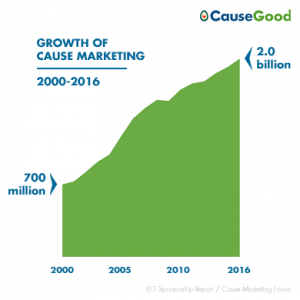

Background: According to the NYT, since 2000 the number of women undergoing breast reconstruction after breast cancer is up 35 percent. In 2015, 106,000 women had reconstruction. Many breast cancer patients report their surgeons did not make it clear that their new breasts would feel numb.

As one can imagine, numbness can be physically and emotionally disorienting for many women. Roni quotes women who’ve injured themselves and not realized it, women who can no longer feel the touch of their children and lovers, and women who feel like they were misinformed when their surgeons told them their breasts would “feel” natural.

Then she digs deeper into that key word: FEEL

Roni spoke to surgeons who explain that when they use the word “feel” in pre-surgery conversations – “as in your new breast will feel natural” – what they mean is that the reconstructed breast(s) will feel natural to other people (aka: men). They aren’t talking about how the breast will feel to the woman herself.*

Doctor-patient convos still centered on what “feels” good to men

Many women don’t realize until after reconstructive surgery that their new breasts will feel numb forever. Some women do regain partial sensation in reconstructed breasts but full sensation is extremely rare due to nerve damage.

My issue is not with numbness. (And, full disclosure, my flat chest has full sensation.) And, as an aside, I’d be curious to know know if flat-chested women are more likely to regain sensation than women who reconstruct.

My point is that plastic surgeons are framing the conversation in terms of what will feel best for men.* And that’s eff-ed up. As I’ve been saying for ages, breast cancer patients can’t make well-informed decisions without accurate and unbiased information. Language that privileges a man’s experience of a woman’s body over her own is biased (to put it mildly).

A woman’s decision to reconstruct is a big one. All reconstructive options require multiple surgeries (even so-called simple implants need to be replaced every 7 to 10 years). Breast reconstructive procedures have unusually high rates of complications, including infection, implant rejection, and lasting pain.

I’m guessing most women would weigh the reconstruction decision differently if they knew in advance their new breasts would feel numb, if their surgeons were able to reframe the conversation around what the new breasts might feel like to the woman herself, not to the man in her life.*

Only when women have complete, accurate, and unbiased information can they make a decision about reconstruction with a clear-eyed expectation about what it will feel like to live in their post-surgical body. Because they are the ones who will be feeling it 24/7 for the rest of their lives.

*In my world, lots of cis-ladies and non-gender-conforming folks touch breasts, but, in the mainstream medical world, the only folks thought to touch women’s breasts are cis-, het-men.