Thirteen years ago, in the spring of 2003, I interviewed Barbara Brenner, then executive director of Breast Cancer Action (BCA). The interview never ran.

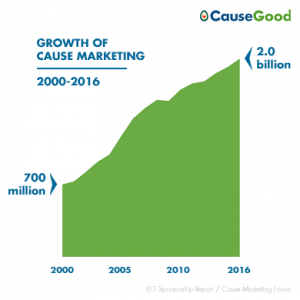

I was an optimistic, young journalist excited about her first investigative assignment. The topic was cause-marketing. The news hook was a brewing controversy surrounding Avon’s 3-day breast cancer events.

I’d pitched and sold the idea to a national women’s magazine. My editor loved it. The magazine slated the article for the October issue — Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

I spent six weeks researching, interviewing, and writing the 3,000-word feature. Brenner was front and center. Her message stressed the importance of women taking back their power from corporate America. I couldn’t believe such a bold, feminist message was poised to reach 1.4 million readers.

Then, a month before publication, my editor called to tell me the magazine killed my story. Avon was a new advertiser and the marketing team didn’t want to tarnish the new relationship. My interview with Barbara sank to the bottom of my hard drive. Until now.

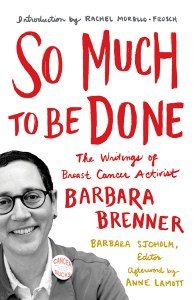

I was reminded of the long-lost interview when, in April, BCA redoubled its efforts to get women to ask 4 questions before walking for charity. Then I found out the University of Minnesota Press was set to publish a collection of Barbara’s writings. Finally, last week, Karuna Jaggar, BCA’s new executive director, penned an op-ed for the Washington Post “breast cancer walks are a terrible way to fight breast cancer.”

So it only seems fitting that, for the first time and with the permission of the kind folks at BCA and Barbara Brenner’s family, I’m posting my long-ago interview with Barbara.* She won a life-long supporter in that 20-minute phone call. And, after all these years, her words ring just as true:

Q: Describe, in a nutshell, your chief complaint with cause marketing.

Brenner: One is the exploitation of a devastating illness by companies. The second is that while we really want people to do something about breast cancer, we want people to do something real. Many of these campaigns give people the illusion that they’re doing something real when they’re not.

Q: What do companies gain?

Brenner: They gain profits. They do this to improve their bottom line. That’s what companies do. They gain a reputation for caring deeply about something other people care deeply about.

Q: How do you respond to those who might say, “who cares if companies make money, at least they’re giving back.”

Brenner: I would say that while I appreciate that point of view, we shouldn’t let companies off the hook. People need to think about whether or not companies using breast cancer to improve their bottom line is really helpful.

Q: What makes breast cancer such an easy target for cause marketing?

Brenner: Breast cancer is a great cause-marketing tool because it’s an issue women care about and women have a lot of purchase power. Plus, it’s about breasts. Breast cancer is relatable in a way, for instance, AIDS never was because AIDS was loaded with sex and sexual orientation. Breast cancer is just the opposite. Yes, it’s loaded because it’s about breasts and America loves that.

Q: Can you speak to what raising money for breast cancer through the sale of lipstick, yogurt, and vacuum cleaners says about how women are perceived by these companies? Is it valid or a conditioned response?

Brenner: It’s valid in that it works. These campaigns communicate that what women can do about breast cancer is to buy things. It’s a disservice to women.

Q: If a woman wants to contribute to breast cancer research, how would you advise her to go about it?

Brenner: Look at what kind of research you want to fund then look at who’s doing that and who doesn’t already have enormous access to money. If you don’t know who’s doing it, contact a breast cancer organization in your area and ask.

Also, think about whether or not the organization is getting any results for the money that is going to them. What can they tell you about how successful their programs are about getting to the bottom of this problem?

Q: Any last thoughts?

Brenner: Research is a big universe. What makes signing up for a walk or sending in yogurt lids appealing is that somebody else is making decisions for us about where to put the money. But as long as we leave those decisions in the hands of those who are not directly affected by breast cancer we will continue to throw money down a black hole. Remember: Activism works by multiplying the affects of a single action. It is the power of individuals to create change.

*Note: The interview has been edited for length.