This week, JAMA Surgery published the final results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium (MROC) — the first comprehensive look at how cancer patients fare (physically and emotionally) after breast reconstruction. The New York Times had excellent coverage (aside from the cringe-inducing ending).

This week, JAMA Surgery published the final results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium (MROC) — the first comprehensive look at how cancer patients fare (physically and emotionally) after breast reconstruction. The New York Times had excellent coverage (aside from the cringe-inducing ending).

Quick summary: MROC researchers looked at 8 different breast reconstructive procedures performed by 57 different surgeons at 11 sites across the US and Canada. They enrolled 2,224 patients and followed them for four years.

Last month, I spoke with Ed Wilkins, MD, MROC’s lead author and a plastic surgeon at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “We designed and conducted MROC because the decision to reconstruct isn’t just one decision, it’s a constellation of decisions,” he said. “And our patients were getting lost.”

Flaps are The Wild West of Breast Reconstruction

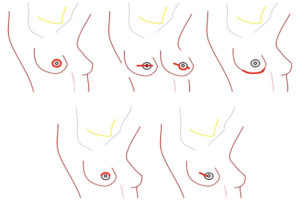

Lost because in recent years plastic surgeons have devised a variety of new ways to rebuild a breast lost to cancer. Implant-based reconstruction has been and remains the most common, but a growing number of women are choosing flap-based surgeries, which are exceedingly more complex.

In flap-based surgeries a plastic surgeon harvests a “flap” of skin, complete with underlying tissue and sometimes muscle, then transfers it to a woman’s chest. The end goal is to cut, mold, and shape the flap into a “breast-like mound.”

Plastic surgeons have long scavenged flaps of tissue from a woman’s abdomen or (in the case of slender women) her mid-back for years. But what is new is the far-flung territory surgeons are inching into. The past few years have seen surgeons taking breast-to-be flaps from a woman’s thighs, buttocks, and (pretty much) anywhere she has something to spare.

Breast Reconstruction Brought to You by Congress

Breast reconstruction rates have skyrocketed since 1998 when the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act was passed. The act mandated that insurance companies pay for reconstruction if a woman lost one or two breasts to cancer. After Congress signed the Act into law, the percentage of women reconstructing after a single mastectomy more than tripled (11.6 percent to 36.4 percent), and those opting to reconstruct both breasts after double mastectomy rose from 36 percent to 57 percent.

One might imagine the numbers would plateau once the backlog of women who’d been unable to afford reconstruction moved through the pipeline, but that’s not what happened. Wilkins notes that not only has the percentage of breast cancer patients undergoing reconstruction crept up every year, but that “most recently, the numbers got a bump from Obamacare, which enabled women who hadn’t had insurance to reconstruct.”

Like any new field, a sudden increase in consumer demand and inflow of cash sparked innovation and surgeons began to design new breast-flap procedures left and right (so to speak). And, naturally, ethical standard bearers in the field are stepping back to measure how patients are faring and what (if anything) needs to be course corrected. That’s how MROC was born.

But…1 in 3 Women Endure Complications

MROC’s most significant initial finding was that up to 30 percent of women had a major complication after surgery. Major complications of breast reconstructive surgery include infection, breakdown of tissue at the incision site, and partial death of the transferred tissue due to low blood supply. One in three women is a jaw-dropping number.

When pressed to defend the acceptability of a 30 percent complication rate from an elective procedure, Wilkins answers ranged from, “Well, everything in life is a risk-benefit analysis,” to “the road to reconstruction is bumpy but we get there,” and, finally, “it’s worth it in the end because reconstruction contributes significantly to mastectomy patients’ qualities of life.”

Why “Quality of Life” Is A Questionable Marker

The dominant cultural narrative toward breast cancer is that a woman is not “whole” until her body looks the way it did before diagnosis. (Caveat being her “clothed body” because an unclothed reconstructed breast will not look the same as a bio-breast.) In the eyes of Western notions of female sexuality, a woman who does not reconstruct her breast is disfigured, less-than, and undesirable. She is not “whole.”

But how does one measure the “psychosocial” impact of breasts?

In the introduction to his MROC Study, Wilkins writes, “Breast reconstruction can improve a patient’s quality of life and alleviate the psychological distress associated with mastectomy.” The evidence he cites is a 1983 Lancet study. It doesn’t take a leap to imagine to guess who is writing the questions on the quality of life studies and how their biases might influence framing and word choice and, therefore, women’s responses.

And, in most cases, they are asking women after the fact if they are happy with their choice. Clara Lee, MD, a plastic surgeon at Ohio University who studies these nuances in decision-making notes, “Most studies take place after women have had surgery and are therefore subject to ‘recall bias.'”

Steven Katz, also at the University of Michigan, studies breast cancer treatment communication, decision-making, and quality of life issues. During the span of his career he has surveyed more than 10,000 women post-breast cancer and reports similar levels of satisfaction in both flat and reconstructed women. “People choose their course and align their perspective with their course. People don’t like to contradict themselves. Regret doesn’t feel good, so naturally we guard against it,” he says. “Practitioners need to remember that quality of life will always be in the eye of the beholder.”

The MROC study is vital and important work. Women will finally be able to compare one surgery vs another. Dr. Wilkins has dedicated his career to reconstructing women’s breasts; he shared that he has done more than 2,000 such surgeries. But Wilkins is a product of his time. (As am I.) With as much as I honor his contribution to breast cancer research, I could almost feel him pat my shoulder as he repeated how bumpy the road to reconstruction is but how dedicated he is to getting women to their final destination.

Final Destination = Breasts at All Costs

Let’s be clear, the final destination is “breasts,” and the bumps he refers to are 4 to 8-hour surgeries, multiple infections, and (in some cases) dying tissue. Even by using the word procedures to describe what in many cases are grueling surgeries performed by the most talented microvascular surgeons in the country is dismissive of the rigor involved and the intensity of the recovery time for the patient.

The MROC study did not include a category for women who chose to go flat after breast cancer. Of course, the point of the study was to compare reconstructive outcomes, but I can’t help but feel it was a missed opportunity to gather much-needed evidence on all the options, not just those that recreate the semblance of breasts.

The authors acknowledged a big limitation of the study was the “exclusion of patients who changed their reconstructive technique (97 patients) and those who experienced reconstructive failure (123 patients).”

The MROC study is a wonderful beginning but, in the hands of practitioners who are blind to their own biases, its utility will be limited.

Comments are closed.