Last week, I unleashed my (not so) inner feminist in an interview with Christie Aschwanden. Christie is not only a top-notch science writer but also a dear friend. She has written extensively about controversial topics in the breast cancer community. She is on #teamscience, which is not an easy team to play for these days. And, so, I deeply appreciate her inviting me to explore some complex ideas I’ve been grappling with these past few months, including how health care providers unintentionally perpetuate systems that harm breast cancer patients . When writing my memoir, FLAT, I aligned closely with the craft of creative nonfiction genre. I worked hard to stay rooted in the roles of character and narrator. Meaning, I didn’t expand my voice or my view beyond the scope of the story and direct connections to the story. So, in some ways, this Q&A with Christie was a welcome exercise as it allowed me to speak in a different register. I got to fully explore some complicated ideas and draw on inspiration I found in Susan Sontag’s essays. I hope you’ll take a look at the Q&A and let me know what you think.

. When writing my memoir, FLAT, I aligned closely with the craft of creative nonfiction genre. I worked hard to stay rooted in the roles of character and narrator. Meaning, I didn’t expand my voice or my view beyond the scope of the story and direct connections to the story. So, in some ways, this Q&A with Christie was a welcome exercise as it allowed me to speak in a different register. I got to fully explore some complicated ideas and draw on inspiration I found in Susan Sontag’s essays. I hope you’ll take a look at the Q&A and let me know what you think.

breast cancer

1 in 3 Women Who Reconstruct Endure Complications

This week, JAMA Surgery published the final results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium (MROC) — the first comprehensive look at how cancer patients fare (physically and emotionally) after breast reconstruction. The New York Times had excellent coverage (aside from the cringe-inducing ending).

This week, JAMA Surgery published the final results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium (MROC) — the first comprehensive look at how cancer patients fare (physically and emotionally) after breast reconstruction. The New York Times had excellent coverage (aside from the cringe-inducing ending).

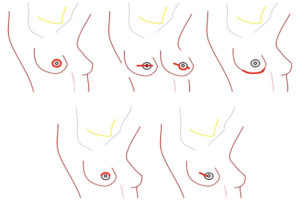

Quick summary: MROC researchers looked at 8 different breast reconstructive procedures performed by 57 different surgeons at 11 sites across the US and Canada. They enrolled 2,224 patients and followed them for four years.

Last month, I spoke with Ed Wilkins, MD, MROC’s lead author and a plastic surgeon at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “We designed and conducted MROC because the decision to reconstruct isn’t just one decision, it’s a constellation of decisions,” he said. “And our patients were getting lost.”

Runner Chooses “Boston Over Boobs”

Today is the annual running of the Boston Marathon, no small affair in my adopted hometown. Last night, I read a feature story in the News Sentinel about a marathoner and breast cancer patient who chose the Boston Marathon over her breast reconstruction.

According to the article, Peg Hoffman of Fort Wayne, Indiana, went through four grueling surgeries in an attempt to reconstruct her breasts after cancer. Here are the two sentences that stood out to me:

“She chose the surgeon’s option for immediate breast reconstruction.”

And then a quote from Peg:

“I went into it (the first surgery) very carefree…but it got scary. I had a number of issues, infections, skin dying, and I had to have three more surgeries to fix these.”

Post-Pink Ribbon

Breast cancer awareness month is waning. Last week, at my neighborhood post office, I stood in line staring at a battered, two-foot-long, cardboard pink ribbon taped to the wall. Holding my nephew’s birthday present, waiting for my turn, gazing at the decoration’s tattered edges and sloppy tape, I felt – nothing.

I am post-pink ribbon. I just don’t give a f**k. Anger spent on pink ignorance zaps my energy. I want to channel my energy into life. Theresa Brown summed up the pink insult in yesterday’s New York Times, “Pink is about femininity; cancer is about staying alive.”

In December 2015, my friend Cindy was diagnosed with breast cancer. She had a lumpectomy, radiation, and chemotherapy. We talked on the phone. We compared notes on treatment side effects. We walked her dog. She got through it with grace and wit. She returned to work. All seemed well.

Six months later she had an odd pain in her rib cage. Worry chafed her voice as she described the sensation. I don’t remember what I said. I tried to be optimistic without being dismissive. We both lived with the fear of metastasis. We both knew what bone pain might mean.

Two weeks ago I was reading Sherman Alexie’s beautiful new memoir, “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me.” when this passage jumped out at me:

Two weeks ago I was reading Sherman Alexie’s beautiful new memoir, “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me.” when this passage jumped out at me:

Nobody defeats cancer. There is no winning or losing. There is no surviving or not surviving. There are only coin flips: heads or tails; benign or malignant; weight loss or bloating; morphine or oxycodone; extreme rescue efforts or Do Not Resuscitate; live or die.

Cindy lost the coin flip. Her cancer had spread to her bones.

Before Cindy was my friend, she was my physical therapist. She restored the range of motion in my left arm after radiation. She released the scar tissue across my chest from my double mastectomy. She reduced the swelling in my arm when lymphedema settled in for a visit. She was one of the most compassionate and talented healers I’d ever met and I’ve met quite a few.

She’d rubbed shoulders with the disease most of her life. Her mother had suffered from breast cancer. Cindy had spent much of her career as a physical therapist helping breast cancer patients regain freedom in their post-treatment bodies.

Cindy was in her late 50s when she was diagnosed. She had a son in college, a daughter in high school. We often talked about the future, her excitement about her new solo physical therapy practice and her dream of spending more quality time with her husband now that her children were grown.

Cindy died this month. She was 61.

Reject the commodification of women’s pain

Anyone who has lost a loved one to this disease knows breast cancer is not pink; to festoon kitty litter, vibrators, and fire engines with pink ribbons eats away at the gravitas of this disease. It’s the opposite of awareness; it’s erasure.

Breast cancer is about staying alive. Who lives and who dies has nothing to do with who “fights like a girl” or who “kicks cancer’s ass.” Staying alive is a coin toss. This year 40,610 women in the U.S. will lose their coin flip with breast cancer. Let’s focus on them.

Numbness and Reconstruction

Last week the NYT ran another feature by Roni Caryn Rabin: After Mastectomies, an Unexpected Blow: Numb New Breasts. Roni is one of the few mainstream journalists asking tough questions about breast cancer realities. Last fall, she penned a thought-provoking piece about folks who go flat post-breast cancer. Now, her first follow-up is a well considered examination of a common problem – numbness after reconstruction.

Background: According to the NYT, since 2000 the number of women undergoing breast reconstruction after breast cancer is up 35 percent. In 2015, 106,000 women had reconstruction. Many breast cancer patients report their surgeons did not make it clear that their new breasts would feel numb.

As one can imagine, numbness can be physically and emotionally disorienting for many women. Roni quotes women who’ve injured themselves and not realized it, women who can no longer feel the touch of their children and lovers, and women who feel like they were misinformed when their surgeons told them their breasts would “feel” natural.

Then she digs deeper into that key word: FEEL

Roni spoke to surgeons who explain that when they use the word “feel” in pre-surgery conversations – “as in your new breast will feel natural” – what they mean is that the reconstructed breast(s) will feel natural to other people (aka: men). They aren’t talking about how the breast will feel to the woman herself.*

Doctor-patient convos still centered on what “feels” good to men

Many women don’t realize until after reconstructive surgery that their new breasts will feel numb forever. Some women do regain partial sensation in reconstructed breasts but full sensation is extremely rare due to nerve damage.

My issue is not with numbness. (And, full disclosure, my flat chest has full sensation.) And, as an aside, I’d be curious to know know if flat-chested women are more likely to regain sensation than women who reconstruct.

My point is that plastic surgeons are framing the conversation in terms of what will feel best for men.* And that’s eff-ed up. As I’ve been saying for ages, breast cancer patients can’t make well-informed decisions without accurate and unbiased information. Language that privileges a man’s experience of a woman’s body over her own is biased (to put it mildly).

A woman’s decision to reconstruct is a big one. All reconstructive options require multiple surgeries (even so-called simple implants need to be replaced every 7 to 10 years). Breast reconstructive procedures have unusually high rates of complications, including infection, implant rejection, and lasting pain.

I’m guessing most women would weigh the reconstruction decision differently if they knew in advance their new breasts would feel numb, if their surgeons were able to reframe the conversation around what the new breasts might feel like to the woman herself, not to the man in her life.*

Only when women have complete, accurate, and unbiased information can they make a decision about reconstruction with a clear-eyed expectation about what it will feel like to live in their post-surgical body. Because they are the ones who will be feeling it 24/7 for the rest of their lives.

*In my world, lots of cis-ladies and non-gender-conforming folks touch breasts, but, in the mainstream medical world, the only folks thought to touch women’s breasts are cis-, het-men.