Last week, I unleashed my (not so) inner feminist in an interview with Christie Aschwanden. Christie is not only a top-notch science writer but also a dear friend. She has written extensively about controversial topics in the breast cancer community. She is on #teamscience, which is not an easy team to play for these days. And, so, I deeply appreciate her inviting me to explore some complex ideas I’ve been grappling with these past few months, including how health care providers unintentionally perpetuate systems that harm breast cancer patients . When writing my memoir, FLAT, I aligned closely with the craft of creative nonfiction genre. I worked hard to stay rooted in the roles of character and narrator. Meaning, I didn’t expand my voice or my view beyond the scope of the story and direct connections to the story. So, in some ways, this Q&A with Christie was a welcome exercise as it allowed me to speak in a different register. I got to fully explore some complicated ideas and draw on inspiration I found in Susan Sontag’s essays. I hope you’ll take a look at the Q&A and let me know what you think.

. When writing my memoir, FLAT, I aligned closely with the craft of creative nonfiction genre. I worked hard to stay rooted in the roles of character and narrator. Meaning, I didn’t expand my voice or my view beyond the scope of the story and direct connections to the story. So, in some ways, this Q&A with Christie was a welcome exercise as it allowed me to speak in a different register. I got to fully explore some complicated ideas and draw on inspiration I found in Susan Sontag’s essays. I hope you’ll take a look at the Q&A and let me know what you think.

Choosing Not to Reconstruct

1 in 3 Women Who Reconstruct Endure Complications

This week, JAMA Surgery published the final results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium (MROC) — the first comprehensive look at how cancer patients fare (physically and emotionally) after breast reconstruction. The New York Times had excellent coverage (aside from the cringe-inducing ending).

This week, JAMA Surgery published the final results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium (MROC) — the first comprehensive look at how cancer patients fare (physically and emotionally) after breast reconstruction. The New York Times had excellent coverage (aside from the cringe-inducing ending).

Quick summary: MROC researchers looked at 8 different breast reconstructive procedures performed by 57 different surgeons at 11 sites across the US and Canada. They enrolled 2,224 patients and followed them for four years.

Last month, I spoke with Ed Wilkins, MD, MROC’s lead author and a plastic surgeon at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. “We designed and conducted MROC because the decision to reconstruct isn’t just one decision, it’s a constellation of decisions,” he said. “And our patients were getting lost.”

Flat and Proud

I have zero tolerance for hiding. I came out to my father when I was 22. His response? “This can be our secret.”

I have zero tolerance for hiding. I came out to my father when I was 22. His response? “This can be our secret.”

Don’t worry — he and I have worked through it (hi dad!) — but his first reaction was to ask me to hide myself (to buy into my shame) to spare himself and others the discomfort of seeing my true self.

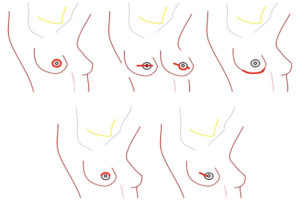

Fifteen years later, I was diagnosed with breast cancer, and I heard a hint of my father’s voice in the words of the plastic surgeon. He offered to reconstruct my breast by carving out a slab of my back muscle, wrapping it around my front, and tucking it over an implant, like a steak over a tennis ball. (Called a latissimus dorsi flap, the surgery is one of the most common reconstructive options after breast cancer.)

“Isn’t that back muscle doing something?” I asked.

“You’ll look normal in clothes,” he shrugged. “That’s all most women want.”

Really? Is that really ALL most women want?

The Decision to Go Flat

Recently, Florence Williams interviewed me for her Audible original series podcast Breasts Unbound. Florence Williams is a science writer extraordinaire and author of several award-winning books including Breasts: A Natural and Unnatural History (W.W. Norton 2012).

Click here to listen. My segment is 22 minutes into the podcast. I know not everybody’s got that kinda time, so I’ll see about getting a transcript. But, in the meantime, here are a few of my talking points.

- My hope in writing FLAT was (is) to expand the conversation around options post-breast-cancer diagnosis. When I was diagnosed in 2009, I was pressed against cultural norms and assumptions of the importance of breasts and other people’s ideas about “what makes a woman.”

- The predominant (and patriarchal) assumption is that breasts are paramount to a woman’s sexuality. Therefore, folks go straight from the breast cancer surgeon’s office to the plastic surgery consult without question. Patients are rarely encouraged to think about what they want for themselves versus for their partners and/or so they can pass in public as a woman untouched by cancer.

- I applaud folks having the choice to reconstruct and the fact that health insurance companies are required to pay for reconstruction post-cancer. But breast cancer patients can’t make a fully informed choice unless they know their options. For example, I saw four different surgeons. Each described various reconstructive scenarios. Going flat was never mentioned.

- Also never mentioned by the four surgeons were the risks of reconstruction, such as the high rates of complications and infections. Even under the best circumstances, most implants must be replaced every 8 to 10 years. A breast cancer patient who chooses implants as part of her reconstruction consigns herself to a lifetime of maintenance. This is no small thing.

- Almost 40 percent of women in the United States who undergo mastectomy for breast cancer do NOT reconstruct, according to a 2014 study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. That’s 4 in 10 women. Other studies suggest the number is even greater. Yet, when we see representations of breast cancer survivors in the media they ALWAYS have breasts. Where are the 40 percent? Why are they invisible?

My FLAT Essay in “O, The Oprah Magazine”

My essay, “Learning Curve,” about going flat after breast cancer and how the decision complicated my relationship to fashion is in the March 2017 issue of O, The Oprah Magazine! A big THANK YOU to the editors at O for publishing an essay by an openly queer writer, an essay that pushes against the mainstream narrative of reconstruction.

I’ve been writing for women’s magazines for nearly 20 years and this is the first time I’ve been allowed to be “out” in an article for a women’s glossy. In the past, any reference to my queerness or my same-sex partner would be edited out either for “space” or because “our readers can’t relate.” Thank you Oprah editors for helping to dismantle this barrier in women’s media.

About this essay: the assignment editor asked for personal essays from writers who felt like their sense of personal style (internal) didn’t align with their fashion choices (external). I chose to write about how my flat chest means that I present to the world as a tomboy, even though I feel very feminine on the inside.

Here’s an excerpt from my FLAT pitch:

In the weeks after my surgery, I took to wearing bulky sweaters. My preferred post-mastectomy colors were black and charcoal grey as they best camouflaged “the situation,” a phrase I adopted from the reality show Jersey Shore. In those first few months I tried to shop for new clothes but nothing feminine fit “the situation” because, of course, women’s clothing designers assumed that women have breasts. Material meant to cover a normal woman’s curves would gather and bunch on my chest like two wilted corsages. Tailored tops and jackets with darts were a non-starter. Breast cancer patients in online forums advised women like me, women with misshapen chests, to wear small, busy patterns, such as zigzags, houndstooth, and even tie-dye. A month after my double mastectomy, I took their advice and bought a tie-dyed shirt off the clearance rack at Target in Bloomington, Indiana. I wore it for the rest of the summer.

Here’s a pic of the essay in the magazine.